- By Dan Veaner

- News

Print

Print

| January 8, 2016 - A successful rescue of 17 Lansing mine workers at the Cayuga Salt Mine Thursday morning has revived interest in this story from 2012, which takes you on a tour of the deepest rock salt mine in North America. | ||

The mine spans from the topside Portland Point facility under the lake to as far north as Bill George Road near Swayze Road. Currently held mining rights will allow Cargill to expand farther north to Milliken Station before negotiating with the State again for more area.

Elevator shafts take miners almost a half mile underground. A hoist is used to pull trucks and equipment into the large elevator cage.

Elevator shafts take miners almost a half mile underground. A hoist is used to pull trucks and equipment into the large elevator cage.Currently there are three shafts, two of which are actively in service. Once transports people and equipment to and from the mine. The tallest is used to bring salt to the surface, where is is stored in enormous piles. The third is used mainly to supply air.

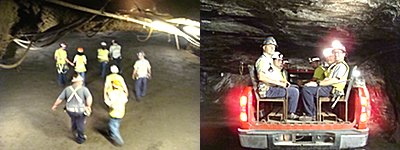

Driving to work at Portland Point is only the beginning of the commute for mine workers. The nearly half-mile elevator descent takes about five minutes, and then miners still have a 30 to 40 minute commute to the work sites in small open trucks. A fleet of small vehicles that look like the offspring of pickup trucks that mated with golf carts takes workers on an ever-expanding commute.

Stepping out of the elevator is only the first part of going to work. There is still a 30 to 40 minute drive to the active mine areas.

Stepping out of the elevator is only the first part of going to work. There is still a 30 to 40 minute drive to the active mine areas.Miners work in three production shifts, Monday through Friday, and maintenance shifts on weekends. At any given time there may be around fifty people below ground. Employees have to be independent and resourceful, generally working in groups of only two or three.

| When Town Historian Louise Bement was a teacher in the Lansing schools in the mid '80s she and her fourth grade class wrote a 48 page booklet, 'The Rock Salt Mine (1916-1985)'. Cargill Mine Manager Russ Givens was recently given a copy. He says it is the best summary of the mine's history available. "That's the best history of this place that I've seen yet," he says. "She did a nice job with it." | ||

The tunnels are made of a series of 'rooms' that are designated by pillars of salt at the four corners. Miners use two reflective bars placed in the ceiling by surveyors to sight the next 'room' to be mined so that tunnels are cut in a straight line.

Off the main tunnels are series of seven smaller tunnels where the salt is currently mined. These are also made of a series of rooms held up by pillars that make the mine look like a giant underground parking garage. Seven-tunnel sections are separated by large unmined blocks in the active section of the mine.

"The unmined blocks are key to the overall mine stability," Mine Manager Russ Givens explains. "The pillars control the roof within the mined-out area."

An electrical switching room controls electricity that is sent to large transformers where they are needed around the mine.

An electrical switching room controls electricity that is sent to large transformers where they are needed around the mine.The pillars are scraped periodically to remove material that has loosened and may become a hazard. Some salt is white, while some is made of transparent crystals with some dirt mixed in that makes it appear black. The scraping process gives salt pillars a striped look with the white showing through darker salt.

A hoist is installed at the top of the elevator cab so these vehicles and other small equipment can be fit on end in the elevator. Everything in the mine has to fit in this elevator. Smaller vehicles are hoisted in on end. Large equipment must be brought down in pieces, that are welded back together once they each the mine. They look like heavy equipment version of Frankenstein monsters with welding seams forming huge scars along the truck surfaces. This equipment can cost from $600,000 to loaders costing more than a million dollars, and the disassembly/assembly process adds considerably to the price tag.

Entering the expansive shop area

Entering the expansive shop area Inside the workshop

Inside the workshop

Along the main tunnel is an expansive workshop where equipment is welded together and maintained. Machine parts are strewn along mine walls, and offices look like oversized boxes placed here and there around the shop area. An area with a a concrete floor is used for washing equipment, because salt is not a stable surface when wet. A secondary shop is about two miles farther along the route, but most of the maintenance is done in the main shop.

"One of the unique things about our operation is we're constantly getting bigger," Givens says. "We're forever moving and adding onto our electrical systems, our conveyors, we have to push air a little further... That's one of our challenges that we're always going further away. We need power, we need air, and we need the ability to get everyone out of this mine in less than an hour."

The luchroom

The luchroomNear the active mining area an office area has been built on a large skid so it can be dragged closer to new work areas as the mine is extended. There are no walls, but tables, computers, break area with coffee makers, bulletin boards, and a microwave are part of what passes for a company lunchroom. Computers are contained in enclosures that protect them from dust and erosion. 4200 volts are sent to huge portable transformers that convert the power to a usable 480 volts needed for the equipment, and, in some cases, to 110 volts for small appliances.

Once it is lined up with the rock wall this machine automatically bores holes for blasting. Inset shows six expansion holes.

Once it is lined up with the rock wall this machine automatically bores holes for blasting. Inset shows six expansion holes.

Large machinery is portable, enormous trucks with drills or other machinery built in. One drills holes in the salt face to insert explosives and provide expansion space needed for the blast. Surveyors install two reflectors in the ceiling that miners use like a gun sight to line up the machine to drill blasting holes that will perfectly center the next room. Three augers drill up to 21 foot long holes with smaller blast holes above and below them.

The drilling is completely automated, making three long, narrow holes at a time, then retracting the augers and sliding along a rail to drill the next three. The machine can drill a 1 5/8 inch diameter hole 22 feet deep in 52 seconds. The salt is about the same hardness as concrete. Cargill has used this technology for almost 20 years, when it replaced technology from the 1930s. Machines are run with remote controls that replace older equipment that required miners to operate up to twenty hydraulic levers in a hot cabin.

Other large machines include one that inserts steel rods into the ceiling to help support it, and enormous loaders with giant buckets for moving salt from big piles where explosive charges deposit the large chunks.

The machine at left drills holes into the ceiling to insert steel bolts that help support the ceiling. It is operated using a remote control (right).

The machine at left drills holes into the ceiling to insert steel bolts that help support the ceiling. It is operated using a remote control (right).The loaders take the salt to crushers that break the salt down to chunks smaller than a football and loads conveyor belts with about 600 tons of salt per hour. Ceilings have to be cut higher than normal to make room for the buckets on the loaders to reach above the crusher and conveyor belts that carry the salt to the main tunnel. They deposit it on mainline conveyor belts that take the salt through a crushing screen plant and eventually to an elevator shaft to be hoisted to the surface.

The screen plant is so high that it spans three veins of salt.

The screen plant is so high that it spans three veins of salt. These filters (at left) have rubber balls inside that bounce around as the salt is being screened. This keeps the filters from getting clogged. Once it has been screened it is dumped onto conveyor belts that bring it to a shaft in which it is brought up to the surface.

These filters (at left) have rubber balls inside that bounce around as the salt is being screened. This keeps the filters from getting clogged. Once it has been screened it is dumped onto conveyor belts that bring it to a shaft in which it is brought up to the surface.The conveyor belts and screen plant is located in the exhaust tunnel that returns circulated air. It is several stories high, traversing three veins of salt. It is a series of crushers, conveyor belts, and filters that separate the salt from stone and reduce it to the designated size, also filtering out particles that are too small. Cargill's quality specification for the final product is 95.5% sodium chloride with salt crystals larger than sand and smaller than a half inch.

In case of emergency the lights are turned off, a simple and effective way to alert everyone that they must evacuate immediately. They return to their vehicles using their helmet lights and drive back to the elevator, the only light coming from their helmets and vehicle headlights.

Like most of us the mine gets electricity from NYSEG, and central New York weather is such that Tompkins County suffers power outages. A few weeks ago storms caused blackouts that turned out the lights for 4000 Ithaca area customers, including Cargill. That meant evacuating the mine, and it caused problems in the electrical system that were still being addressed this week. Three days later the mine lost power again, and again the mine had to be evacuated.

At left, parts storage. All replacement parts must be stocked underground. Once machines are in the mine they cannot be brought to the surface for maintenence. At right, bathroom facilities are not luxurious in the mine.

At left, parts storage. All replacement parts must be stocked underground. Once machines are in the mine they cannot be brought to the surface for maintenence. At right, bathroom facilities are not luxurious in the mine.This winter mild weather forced the company to lay off about 60 people for about two months. The company did what it could to help these employees, continuing their health care policies and also paying their premiums. 14 chose to volunteer in the mine, taking care of projects they didn't have time to do when the mine was at full production. And when the company could afford to bring these employees back, all but one returned.

"Joyce Stern, who runs the screen plant on the day shift, had a lot she wanted to do," Givens says. "We (employees who were not laid off) also got a lot of projects done, some of which we weren't sure how we were going to make the time to do them. We made use of the time pretty well."

The mine is 2300 feet below the surface. The original mine shaft was completed in 1918, when mining commenced under the Town of Lansing, as much as 2800 feet underground in some places. But today the entire active area is beneath Cayuga Lake. It is the deepest rock-salt mine in North America.

Givens notes that mining under the lake has two advantages: mineral rights only have to be purchased from one landowner, New York State. And a lake weighs less than solid rock, which means less pressure to fight against when drilling through the earth and holding up the mine ceiling.

This is what salt looks like after it has been blasted. Some is the familiar white, while other pieces are made of clear crystal with some dirt mixed in that makes it appear black.

This is what salt looks like after it has been blasted. Some is the familiar white, while other pieces are made of clear crystal with some dirt mixed in that makes it appear black.About half of the salt produced in Lansing is sold to the State of New York for local use. The Town of Lansing is among Cargill's customers. In the past the highway department simply trucked the salt about a mile from the mine to the town salt storage building. But Lansing does better to purchase the salt on State bid, rather than directly from Cargill.

The other half is sold to municipalities in Vermont, Virginia, and North Carolina, and sold as packaged rock salt under the Cargill label, with some sold under the Agway label.

If you are one of the growing number of people who prefer to buy local, it doesn't get any more local than Cargill. Whether you are driving around Tompkins County or melting the snow on your sidewalk, it is almost certain that you are using the salt that comes from the Lansing mine.

"Most of our market is local," Givens says. "It's direct truck, right out of the mine to the customer. It's unique that we fit into this area, and we're keyed into the business in this area."

Photos by Karen Veaner

v8i36