- By Dan Veaner

- Around Town

Print

Print  Five Lansing Monarch Butterflies began their long journey from Raymond C. Buckley Elementary School nearly 3,0000 miles to Michoacán, Mexico a week ago last Monday. Young scientists tagged the butterflies while learning about the striking orange and black insects that had grown from egg to larva to butterfly in their school. Those five butterflies will fly to Mexico to mate, but it will take five generations to get back to Lansing.

Five Lansing Monarch Butterflies began their long journey from Raymond C. Buckley Elementary School nearly 3,0000 miles to Michoacán, Mexico a week ago last Monday. Young scientists tagged the butterflies while learning about the striking orange and black insects that had grown from egg to larva to butterfly in their school. Those five butterflies will fly to Mexico to mate, but it will take five generations to get back to Lansing."This is part of a project from North America -- Canada, the United States and Mexico -- of thinking about an ambassadorship, using this insect to teach kids about the international world," explains Lansing Elementary Special Education teacher Wendy Wright. "It also brings in geography and, certainly, citizenship. It brings in math, because we figure out how far the butterfly is going to fly from Lansing to Michoacán, Mexico."

Wendy Wright's class learns about Monarch butterflies. (Inset) Participating in a citizen science project called Monarch Health, a student tests the monarch for OE (a parasite).

Wendy Wright's class learns about Monarch butterflies. (Inset) Participating in a citizen science project called Monarch Health, a student tests the monarch for OE (a parasite).Wright says the butterflies take advantage of wind currents to glide most of the way to Michoacán. Once there they cluster together for warmth in the high altitude forest, blanketing the trees in orange. In February they reproduce. Then the long, five-generation journey home to Lansing begins.

"The reason this is a great opportunity is it allows kids to be real scientists," Wright says. "It’s citizen science. We tagged the monarchs with tags that come from the University of Kansas. They have numbers on them. We put them on their wing and then you send them off. Say she gets hit by a car or the wind is not right or there is not enough nectar and she dies… if she has a sticker they get the data and they can see how far she has come. Web sites keep track of the tags. You can post the tag number, and schools will be looking and see if it’s their tag."

Monarchs require milkweed, so Wright looked for eggs in the milkweed in her own yard. She brought them to school to work mainly with third graders, although the whole school was included in the project. Kids learned about how the butterflies grow from egg to chrysalis to butterfly, how to identify milkweed, to tell the males from the females, and how to tag the insects and why that helps scientists learn about their migration.

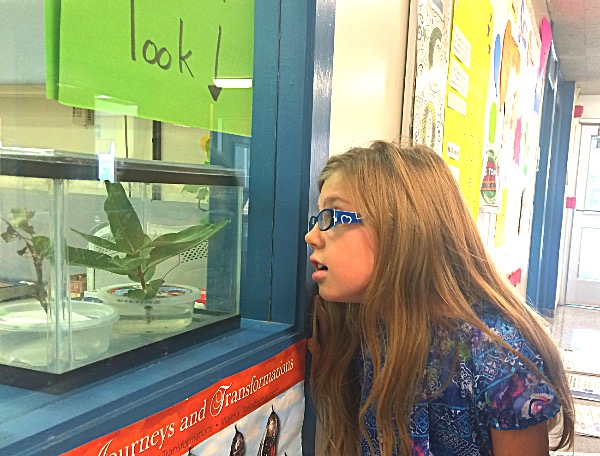

One terrarium was kept in the school office so all students, teachers and staff could watch a monarch butterfly develop from egg to butterfly before being released into the wild for a nearly 3,000 mile journey to Mexico.

One terrarium was kept in the school office so all students, teachers and staff could watch a monarch butterfly develop from egg to butterfly before being released into the wild for a nearly 3,000 mile journey to Mexico.They also learned a bit about Monarchs' health.

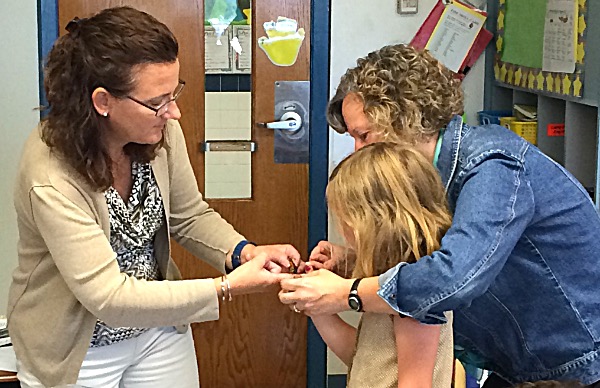

"The second part of citizen science they participated in is OE (ophryocystis elektroscirrha)," Wright says. It’s a parasite. If there are too many it makes the monarch too weak to fly. it doesn’t kill them — it’s like when an animal has too many ticks or fleas. It doesn’t kill the dog, but it’s too weak."

Wright got the idea for the Monarch unit over the course of four summer sabbaticals focusing on internationalizing curriculum and looking for best practices that could be applied predominantly to the third and fourth grades. She looked for ways to connect Spanish and how to connect Lansing to Mexico and South America with an engaging topic. When third grade teachers asked if she had new information to augment their Mexico study unit this year, she was ready.

"I said, 'you won’t believe it — I have this little ambassador that is two inches by three inches'", she says. "It’s the monarch butterfly."

A second grader tagging a Monarch butterfly.

A second grader tagging a Monarch butterfly.The butterflies are decorated by each student to make them unique, and the student's first name and the school address is written on it. They are mailed from all over the United States and Canada to a central location in Minnesota, eventually arriving in Mexico. Children that live near the sanctuaries keep track of them as part of their own school projects. The paper butterflies are counted and and mixed up. The school will receive a package of somebody else’s butterflies with the addresses marked on them so they can track the paper butterfly's migration on a map.

"A package arrives just in time for Cinquo De Mayo," Wright says. "That’s just about the kickoff to their Mexico unit in Lansing."

A class takes its butterfly outside to release it. When weather and wind conditions are right, the butterflies begin their journey to Mexico.

A class takes its butterfly outside to release it. When weather and wind conditions are right, the butterflies begin their journey to Mexico.Now that the butterflies have been released the kids will study decomposers next week. The unit, called 'Dead or Alive?' will have students studying logs, taking them apart and examining them for decomposers with magnifying glasses.

A few years ago Wright visited the West Coast to see the smaller western Monarch population, which doesn't make it as far as Mexico. Wright says that the more spectacular eastern migration is in danger because conditions for milkweed are being eroded, and the Mexican forests are equally being diminished. The Mexican government is working with environmental groups to replace damaged trees, as well as to encourage communities to protect them. Illegal logging was blamed for 15% of the lost hectares last winter. Weather is another hazard to the Monarch population. Last year 7% of the 84 million butterflies that made it to Mexico were killed by storms.

"You need six hectares of Oyamel fir trees to sustain the population," she laments. "Last year it was 1.4. That’s how bad it is."

But reports show that replanting efforts are beginning to replace the lost acreage, though only approximately half has been restored so far. Scientists are also encouraging people in the northern potrions of the migration to plant more milkweed.

With that goal Wright got a grant for $1,000 to start a butterfly garden at Lansing Elementary. She hopes milkweed in this garden will attract new butterflies to lay eggs so future classes can study Monarchs. But the citizen science doesn't stop there. Part of the study includes a 'symbolic migration' of paper butterflies created by each Lansing student and students across North America.

Wright is planning a visit to the Monarch sanctuary this February. She will fly to Mexico City, ride two and a half hours, then hike up the mountain the next day. There she will see hundreds of thousands of Monarch butterflies that have migrated from all over North America. She plans to post blog entries while she is gone so kids at home can share the Mexico part of the Monarch experience.

She is also part of the Monarch Teacher Network, for which she teaches teachers how to raise Monarchs in their own schools. But the fun part is guiding her elementary students as they do real science that is part of a world community of young and adult citizen scientists.

"I love the excitement, the engagement," Wright says. "These kids are so engaged. Many of them don’t seem to have a lot of experience with insects. They have great questions. And the teachers get excited. Everyone is so excited about an insect. That’s what’s so amazing."

v12i38