- By Dan Veaner

- Around Town

Print

Print

Slogging through the rain forest for two and a half hours on foot to go to a one room schoolhouse isn't everybody's cup of tea. It's muddy, there are no roads, and you have to carry everything you want to bring with you. But that is exactly what two Ithaca High School students plan to do. Russ Sternglass (18) and Golda Rosenfield (18) will be leaving for the Cabecar Indian Village in the middle of Costa Rica on February 13 to share music and art with children at two Indian schools there.

The schools are one room school houses, one four old and the other built last year, largely from donated money. "We'll drive a bus to the edge of the world, through the mountains and through the rain forest until we get to the center of the Indian reservation," says Casey Carr, Sternglass's mother. "The Indians have been self sufficient so far. But since they've been crammed into such a small space, they've eaten all of the wild animals on the reservation in order to survive. Now they're trying to survive by growing crops. So one of the reasons for these schools is to try to teach the children how to be environmentally healthy and self sufficient at the same time. Otherwise they will wipe out the little that they've been allowed to have."

Sternglass, who plans to study music therapy in college next year, will be bringing percussion instruments for the children that he hopes will bridge the language gap and encourage them to share their native music. "It's a way for us to communicate, because we don't have a common language," he says.

In fact, communicating is a challenge, because the Cabecar is obscure. When visiting the school the Americans will speak in English. Someone who speaks English and Spanish will accompany them to translate what they say into Spanish. The teacher from the school speaks Spanish and Cabecar, so will translate to Cabecar. And then back the other way. "They speak Spanish primarily, but the Cabecar people are trying to keep their language alive," Sternglass says. "There is a guy who is transcribing the language into Spanish and English in an effort to save it, because it could be totally extinct in ten or twenty years."

Sternglass says that playing percussion together will be a more direct way of communicating. He hopes to make his workshop a music exchange, sharing music he likes with the children, and getting them to share their music. "It's the first time that a musical instrument exchange has ever happened," Carr explains. "We always bring music down to them, but we never see what they can do for us. Giving them percussion instruments will really help, because we can put them into the hands of the kids and see what they can do."

The instruments are being donated by McNeil Music of Ithaca , Toko Imports, and Hickey's. When Sternglass decided to try the music program he approached his long time friends at McNeil Music, an institution in the Village of Lansing. "I've been buying drum equipment here since I was six or seven years old, Sternglass says. "It's right up the street from where I live. It's always been a really great place with really nice people. It's locally owned so you're keeping revenue dollars in the city as opposed to buying online. It's great to support a local business and they're doing really great things in the community."

The instruments are being donated by McNeil Music of Ithaca , Toko Imports, and Hickey's. When Sternglass decided to try the music program he approached his long time friends at McNeil Music, an institution in the Village of Lansing. "I've been buying drum equipment here since I was six or seven years old, Sternglass says. "It's right up the street from where I live. It's always been a really great place with really nice people. It's locally owned so you're keeping revenue dollars in the city as opposed to buying online. It's great to support a local business and they're doing really great things in the community."

He approached Chris Mazer and Don Pharaoh about donating instruments, and they put him in touch with owners Dave and Teresa Bulatek. "I sat down with my wife and talked about it," Bulatek says. "Together we talked about what would work best for the children and proceeded that way."

They came up with about two dozen instruments, rattles and bells, and six tote bags. Carr says the bags will mean a lot to the children, who have to carry everything when they walk to school through the jungle.

Rosenfield will participate in another kind of art exchange. Using materials donated by the World Awareness Children's Museum in Glens Falls, NY, she will work with children on drawings based on their everyday life. She'll bring pictures by American children depicting their lives to give to the Cabecar children, and then bring back the Costa Rican kids' art to share with kids in the U.S.

"I'm really excited about this project," she says. "Recently I have been volunteering in the art room at Northeasteast Elementary School. To see the different levels of artistic development is really interesting to me. My mother is an art teacher, and my grandmother is an art teacher, so that may be the direction I am going in."

The Bulateks have been generous to the community, offering discounts on instruments to local schools, and loaning instruments and sound equipment to WVBR's Crossing Borders, the veterinary auction at Cornell, a local Spanish theater group, a women's chorus group at Ithaca College, Ithaca Festival, and some school programs. Accomplished musicians themselves, their employees are well known as musicians in local bands.

Carr learned about the Cabecar Indian Village through her friendship with another local musician, Harry Aceto. He is bassist for the Vermont-based Clayfoot Strutters , a contra-dance and party band. The band has been conducting a dance camp in Costa Rica for a half dozen years, and two years ago Carr went along. She liked it so well that she went again last year and plans to go again this month. "We try to support the schools with music and art and sports things," she says. "Because they have nothing. They only have what they can make from what they can find in the forest. Their houses, their eating equipment, everything."

Sternglass plans to bring a pair of his own bongo drums to play, which he will have to carry himself to the one school, and on horseback to the other school that is too far to walk to. But after playing in local bands and teaching drums to children here, he is excited about meeting children from another culture and communicating through music. "I'm looking forward to the rain forest and the sanctuaries," Sternglass says. "And being away from all this commercialism. Just going out and seeing how people do it without TV and advertisements."

----

v4i5

The schools are one room school houses, one four old and the other built last year, largely from donated money. "We'll drive a bus to the edge of the world, through the mountains and through the rain forest until we get to the center of the Indian reservation," says Casey Carr, Sternglass's mother. "The Indians have been self sufficient so far. But since they've been crammed into such a small space, they've eaten all of the wild animals on the reservation in order to survive. Now they're trying to survive by growing crops. So one of the reasons for these schools is to try to teach the children how to be environmentally healthy and self sufficient at the same time. Otherwise they will wipe out the little that they've been allowed to have."

(Left to right) Chris Mazer, Dave Bulatek (standing), Russ Sternglass (sitting) Golda Rosenfield |

In fact, communicating is a challenge, because the Cabecar is obscure. When visiting the school the Americans will speak in English. Someone who speaks English and Spanish will accompany them to translate what they say into Spanish. The teacher from the school speaks Spanish and Cabecar, so will translate to Cabecar. And then back the other way. "They speak Spanish primarily, but the Cabecar people are trying to keep their language alive," Sternglass says. "There is a guy who is transcribing the language into Spanish and English in an effort to save it, because it could be totally extinct in ten or twenty years."

Sternglass says that playing percussion together will be a more direct way of communicating. He hopes to make his workshop a music exchange, sharing music he likes with the children, and getting them to share their music. "It's the first time that a musical instrument exchange has ever happened," Carr explains. "We always bring music down to them, but we never see what they can do for us. Giving them percussion instruments will really help, because we can put them into the hands of the kids and see what they can do."

Russ Sternglass with rattles and bells donated by McNeill Music of Ithaca

He approached Chris Mazer and Don Pharaoh about donating instruments, and they put him in touch with owners Dave and Teresa Bulatek. "I sat down with my wife and talked about it," Bulatek says. "Together we talked about what would work best for the children and proceeded that way."

They came up with about two dozen instruments, rattles and bells, and six tote bags. Carr says the bags will mean a lot to the children, who have to carry everything when they walk to school through the jungle.

Rosenfield will participate in another kind of art exchange. Using materials donated by the World Awareness Children's Museum in Glens Falls, NY, she will work with children on drawings based on their everyday life. She'll bring pictures by American children depicting their lives to give to the Cabecar children, and then bring back the Costa Rican kids' art to share with kids in the U.S.

"I'm really excited about this project," she says. "Recently I have been volunteering in the art room at Northeasteast Elementary School. To see the different levels of artistic development is really interesting to me. My mother is an art teacher, and my grandmother is an art teacher, so that may be the direction I am going in."

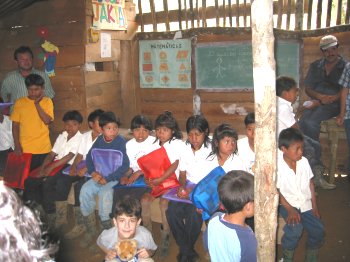

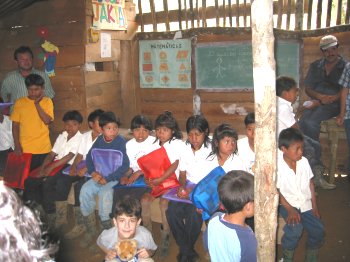

A Cabecar Indian school. (Picture courtesy of casey Carr)

The Bulateks have been generous to the community, offering discounts on instruments to local schools, and loaning instruments and sound equipment to WVBR's Crossing Borders, the veterinary auction at Cornell, a local Spanish theater group, a women's chorus group at Ithaca College, Ithaca Festival, and some school programs. Accomplished musicians themselves, their employees are well known as musicians in local bands.

Carr learned about the Cabecar Indian Village through her friendship with another local musician, Harry Aceto. He is bassist for the Vermont-based Clayfoot Strutters , a contra-dance and party band. The band has been conducting a dance camp in Costa Rica for a half dozen years, and two years ago Carr went along. She liked it so well that she went again last year and plans to go again this month. "We try to support the schools with music and art and sports things," she says. "Because they have nothing. They only have what they can make from what they can find in the forest. Their houses, their eating equipment, everything."

Sternglass plans to bring a pair of his own bongo drums to play, which he will have to carry himself to the one school, and on horseback to the other school that is too far to walk to. But after playing in local bands and teaching drums to children here, he is excited about meeting children from another culture and communicating through music. "I'm looking forward to the rain forest and the sanctuaries," Sternglass says. "And being away from all this commercialism. Just going out and seeing how people do it without TV and advertisements."

----

v4i5