- By Dan Veaner

- Around Town

Print

Print

A Lansing Family Traverses a War Zone to Visit Lansing's Partner School

Harold and Cindy van Es conceived of Partnership of African and Lansing Schools (PALS) four years ago, so it was inevitable that they would visit the school. Over this school year's holiday break they finally got to do that along with daughter Marlene, and sons Martin and Pieter. The trip was a bit more than they bargained for when they found themselves traversing a war zone in Western Kenya. While there they met with Principal William Kabbis, the school board, families, students, and staff at the school. A few weeks ago the Lansing Star sat down with Harold and Cindy as they recounted their adventure.

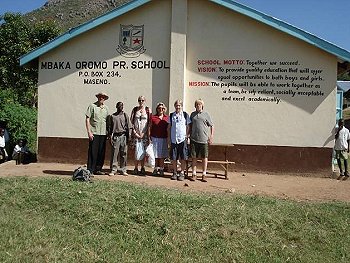

The van Es family meets Mbaka Oromo school families at

an assembly during their visit to Kenya

Between money raised to build classrooms and school project exchange initiatives, PALS has become part of Lansing's culture. Kids look forward to the annual PALS fundraiser where they bounce in the bounce house, run through a sea of balloons, Sumo wrestle, bungee run, and play Guitar Hero. They exchange letters and class projects with their counterparts at the Mbaka Oromo school.

Physical progress at the school has been remarkable, a transformation from mud and dung buildings that had to be constantly rebuilt to 11 classrooms, a library and administration building that will stand for at least 30 years. In addition, the group has begun soil and water conservation work around the school. Academically, students at the school do quite well, placing first in region on academic achievement tests, and often placing students into high schools.

The family left for Kenya on December 27th, intending to go to Nairobi for two days, then go on a short safari. Loaded with donations, they rented a van to carry their stuffed suitcases. " We had a whole suitcase full of just donations," Cindy says. "A lot of people in the community would leave stuff on our front porch. People left Lansing T-shirts. We brought over a lot of Lansing Rec shirts that people left for us. People would leave pencils or markers on my front porch. We wanted to have something school-wise to give every child and toy-wise. We had finger puppets, 500 bouncy balls, 500 pencils, markers, pens. We had teacher supplies, and we had books that people had donated. Everybody's luggage was at the weight limit."

But when they were ready to visit the Mbaka Oromo school, the planned highlight of the trip, they learned that Western Kenya was in turmoil.

Cindy: We planned to stay at the guest house at the university at nearby Kisumu, and work at the school for a week. To plant some trees, and talk to the students and so on. But when this happened that road was blocked due to riots, and burning tires, and people being murdered. So we did the safari and came back to Nairobi and still had a week. We couldn't drive to Kisumu any more.

We had a hard decision to make.

Harold: We went into a war zone. We called the embassy and asked, 'What do you think about us going to western Kenya?' They said, 'We're trying to get people out of there.'

This was a substantial trip and very expensive. We have been saving for two years. We were this close, but we couldn't make it. We talked about it as a family and decided we would take our chances. I called the principal and said, 'we're not sure we'll be able to come.' He said, 'If you can come only for one hour it will be like 100 years to us. The community here is so looking forward to your visit.' That made it difficult for us to not go.

Then we had a difficult time getting back. The political situation deteriorated again. There were riots in Kisumu. We joined a convoy.

Cindy: There were AK47s all around us. We had to be evacuated at one point.

Harold: Fortunately we were never in direct danger, but it was a hard choice.

Cindy: We couldn't stay at the university -- it was closed. We didn't have the van we had hired any more. So the principal arranged for this old car. The radiator exploded on the way. On the way down they lost the clutch. We got taken in by a little women's' cooperative called the Grail Society, which is an international women's society. They took us in and let us stay at this little guest house, because there were no hotels. they were all closed. It was a town the size of Binghamton, but there was only one grocery store that had not been looted.

So we tried to buy as much as they would let us to give to the community. The ATM machines were empty. The gas stations were empty. At least for me all your coping mechanisms are gone. You can't get money, you can't get gas, you can't get food.

Harold: You couldn't get mobile phone cards. It was a real problem because people couldn't communicate.

Cindy: We had brought some cards with us, so we were able to leave them some.

Harold: When we got (to the school) Cindy had tears in her eyes. We got most of the way in a vehicle, so the next day we walked about two miles. We crossed through streams.

The first day we flew from Nairobi to Kisumu. We settled in and then we had a few hours at the school. It was Sunday afternoon, so there was basically nobody else there.

Cindy: They tried to get the van up so we could bring all these suitcases up. The next day we only had a few more little bags. That's why we tried to get up with he van, but it wouldn't make it all the way. So we had to carry all that stuff the rest of the way.

Harold: On the second day all the kids were there and all the teachers, and school board members and the parents. First we had an assembly with speeches. The principal gave a speech, and then we each had to say something.

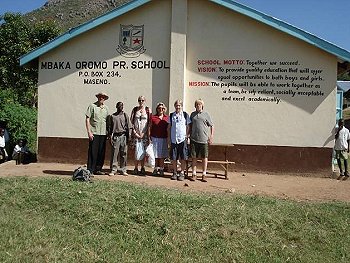

Mbaka Oromo students and their families in front of the

classrooms that PALS built

English is their third language. They have their tribal language, and then they have Swahili, the national language. And then there's English. All adults with some education will know English, so we could communicate quite well.

So we had an assembly and all gave speeches. Then we had a meeting with the parents in one of the classrooms. It was packed to the gills!

Cindy: Some of the older parents and some of the kids only speak Luo. So William would speak to them in Luo. Then there was another man in the community who actually had come to Cornell and gotten a Masters degree and went back. He would translate into Luo if we spoke.

What struck me was when we first looked at the parents we realized that what was so different was that they are old. Many of them are actually grandparents. The AIDs epidemic has taken off our age group. It is largely gone. You don't see many people our age. You see young people and you see very old people.

40% of the kids are orphans, but over half of the parents are truly grandparents, so the audience was filled with 70-year-olds and 80-year-olds. There are not many people our age.

We did the assembly, which was great, because they wanted to hear the children's' voices. I was very proud of my kids, because they're not used to giving speeches. The funny thing is that the little kids kept pointing at the boys. First of all they are big and blond. Then we realized they'd never seen braces. There were these white kids with metal teeth!

When William, who is actually kind of a small man, realized that our Pete -- who is big even by American standards -- was 13 and would be in that school if he lived there, he just couldn't get over that fact! He made all the other boys in that school who are 13 come and stand next to Pete to show ho huge he was!

They are very direct! And they were very surprised that I am a math teacher. 'Look at this woman! This woman is a professor. This woman does math!'

Harold did a great thing. Their school motto is 'Together we succeed'. Harold said, 'How about we all hold hands? It was just magical!

Harold: 400 hundred people are all holding hands and we raised our hands up and said, 'Together we succeed.' That was a very powerful moment, especially because we got so much accomplished and they felt so strongly about their connection to Lansing. And the difficulties that we had in getting there made a deep impression on them.

Cindy: The Africans are very formal. They like speeches, so there was another speech for the parents. But at one level it was gratifying for us beyond those sort of good feelings that we can assure everyone that that money made it there. The classrooms are there. You always wonder...

We saw them, and he talked about it to the parents, so if there were anything going on it wouldn't be that public.

Harold: There was a certain amount of money that went over there. And then you see eleven classrooms, a library, an administration building. Well, if you can build a classroom for $5,000 and you see the classroom, then you know the money is being spent with no creaming off. Everything was very open and above the table.

Cindy: My kids were all looking at their watches, timing how long it would take me to cry. (Laughs) I think Marlene won! It was overwhelming, because we've spent a lot of our time and energy thinking about this. you know it's real, but to actually see it and meet the people. People who are so gracious. They would come up and they knew our names and they had been thinking about us and what we did. They really had this sense of we didn't have to do this. Why did we do this?

They feel like Americans are so privileged, why should we care. If I live in a nice house and a nice community and we have good schools, why are we spending time doing this? The fact that we are just makes a huge impression. People would thank us.

The van Es family with Principal William Kabbis

Harold: It's not only because there are classrooms and the library. It is also because it has lifted the spirits of the community. The name Lansing means so much to those people in that whole area. Lansing is a magical name there. You really felt like you really made an impact.

We tried to focus on something that would be durable. These classrooms will be there for 30 years from now.

Cindy: William kept saying, 'This gave us a big boost.' He used that phrase a lot.

You got the sense it gave them a boost emotionally and physically as well as materially. Some people would come up, especially because we made it though all the danger. They's say they were praying for us. And some people literally thought it was a miracle that we had made it.

That's an indescribable thing having somebody look at you and think you are the result of some miraculous thing. I had a very hard time with that. I thought, no, I'm just a little math teacher from upstate New York.

But they just could not believe we had made it. So it added another dimension, that while all this was going on we were still able to get there.

There were some really scary moments. On that tarmac at Kisumu when we weren't sure we'd get out I prayed, 'Please don't let my children get hurt. Let us get out of here.'

When we went back to Kisumu and went to fly home all the riots started, and it was hard. The police are the opposition tribe. The military were coming in, and they're with the President. The people at the airport were taking bribes. So you don't know whether you can trust the airline people, the police, the military -- it's not quite the same as we're used to.

We flew back to Nairobi and then we had to be put in a secure vehicle to get back to our hotel. It's surreal, because you're in this beautiful garden hotel but all this is going on around you. You can see military troops going by and you hear gunshots. We were sitting in this garden area, kind of shaken up. We looked at the table next to us and there was the President of the World Bank, and we went around the corner and there was Desmond Tutu!

Harold: We were watching CNN and they interviewed people and the next morning they would be having breakfast at the next table.

Cindy: It was bizarre in that sense.

The family made it home to Lansing on January 10th. Now they plan to bring Principal Kabbis to Lansing to meet with our principals here and learn about the academic program at our schools. Originally they planned to bring him here this Spring, around now, but because of the unrest in Kenya he could not get to Nairobi to get his passport and visa. The van Ess say that they will use a separate fund donated by the IthacaRotary Club to bring him over.

Meanwhile they are continuing to raise money for the Kenyan school. They hope to fill the new library with books, and even endow a librarian position for it. Meanwhile the couple hopes that other communities will use PALS as a model for their own programs. With one year to go in their five year plan, PALS has largely reached the goals they originally set for the program. It will make a good model for other American schools that want to partner with African schools in need.

----

v4i19

Harold and Cindy van Es conceived of Partnership of African and Lansing Schools (PALS) four years ago, so it was inevitable that they would visit the school. Over this school year's holiday break they finally got to do that along with daughter Marlene, and sons Martin and Pieter. The trip was a bit more than they bargained for when they found themselves traversing a war zone in Western Kenya. While there they met with Principal William Kabbis, the school board, families, students, and staff at the school. A few weeks ago the Lansing Star sat down with Harold and Cindy as they recounted their adventure.

The van Es family meets Mbaka Oromo school families at

an assembly during their visit to Kenya

Between money raised to build classrooms and school project exchange initiatives, PALS has become part of Lansing's culture. Kids look forward to the annual PALS fundraiser where they bounce in the bounce house, run through a sea of balloons, Sumo wrestle, bungee run, and play Guitar Hero. They exchange letters and class projects with their counterparts at the Mbaka Oromo school.

Physical progress at the school has been remarkable, a transformation from mud and dung buildings that had to be constantly rebuilt to 11 classrooms, a library and administration building that will stand for at least 30 years. In addition, the group has begun soil and water conservation work around the school. Academically, students at the school do quite well, placing first in region on academic achievement tests, and often placing students into high schools.

The family left for Kenya on December 27th, intending to go to Nairobi for two days, then go on a short safari. Loaded with donations, they rented a van to carry their stuffed suitcases. " We had a whole suitcase full of just donations," Cindy says. "A lot of people in the community would leave stuff on our front porch. People left Lansing T-shirts. We brought over a lot of Lansing Rec shirts that people left for us. People would leave pencils or markers on my front porch. We wanted to have something school-wise to give every child and toy-wise. We had finger puppets, 500 bouncy balls, 500 pencils, markers, pens. We had teacher supplies, and we had books that people had donated. Everybody's luggage was at the weight limit."

But when they were ready to visit the Mbaka Oromo school, the planned highlight of the trip, they learned that Western Kenya was in turmoil.

Cindy: We planned to stay at the guest house at the university at nearby Kisumu, and work at the school for a week. To plant some trees, and talk to the students and so on. But when this happened that road was blocked due to riots, and burning tires, and people being murdered. So we did the safari and came back to Nairobi and still had a week. We couldn't drive to Kisumu any more.

We had a hard decision to make.

Harold: We went into a war zone. We called the embassy and asked, 'What do you think about us going to western Kenya?' They said, 'We're trying to get people out of there.'

This was a substantial trip and very expensive. We have been saving for two years. We were this close, but we couldn't make it. We talked about it as a family and decided we would take our chances. I called the principal and said, 'we're not sure we'll be able to come.' He said, 'If you can come only for one hour it will be like 100 years to us. The community here is so looking forward to your visit.' That made it difficult for us to not go.

Then we had a difficult time getting back. The political situation deteriorated again. There were riots in Kisumu. We joined a convoy.

Cindy: There were AK47s all around us. We had to be evacuated at one point.

Harold: Fortunately we were never in direct danger, but it was a hard choice.

Cindy: We couldn't stay at the university -- it was closed. We didn't have the van we had hired any more. So the principal arranged for this old car. The radiator exploded on the way. On the way down they lost the clutch. We got taken in by a little women's' cooperative called the Grail Society, which is an international women's society. They took us in and let us stay at this little guest house, because there were no hotels. they were all closed. It was a town the size of Binghamton, but there was only one grocery store that had not been looted.

So we tried to buy as much as they would let us to give to the community. The ATM machines were empty. The gas stations were empty. At least for me all your coping mechanisms are gone. You can't get money, you can't get gas, you can't get food.

Harold: You couldn't get mobile phone cards. It was a real problem because people couldn't communicate.

Cindy: We had brought some cards with us, so we were able to leave them some.

Harold: When we got (to the school) Cindy had tears in her eyes. We got most of the way in a vehicle, so the next day we walked about two miles. We crossed through streams.

The first day we flew from Nairobi to Kisumu. We settled in and then we had a few hours at the school. It was Sunday afternoon, so there was basically nobody else there.

Cindy: They tried to get the van up so we could bring all these suitcases up. The next day we only had a few more little bags. That's why we tried to get up with he van, but it wouldn't make it all the way. So we had to carry all that stuff the rest of the way.

Harold: On the second day all the kids were there and all the teachers, and school board members and the parents. First we had an assembly with speeches. The principal gave a speech, and then we each had to say something.

Mbaka Oromo students and their families in front of the

classrooms that PALS built

English is their third language. They have their tribal language, and then they have Swahili, the national language. And then there's English. All adults with some education will know English, so we could communicate quite well.

So we had an assembly and all gave speeches. Then we had a meeting with the parents in one of the classrooms. It was packed to the gills!

Cindy: Some of the older parents and some of the kids only speak Luo. So William would speak to them in Luo. Then there was another man in the community who actually had come to Cornell and gotten a Masters degree and went back. He would translate into Luo if we spoke.

What struck me was when we first looked at the parents we realized that what was so different was that they are old. Many of them are actually grandparents. The AIDs epidemic has taken off our age group. It is largely gone. You don't see many people our age. You see young people and you see very old people.

40% of the kids are orphans, but over half of the parents are truly grandparents, so the audience was filled with 70-year-olds and 80-year-olds. There are not many people our age.

We did the assembly, which was great, because they wanted to hear the children's' voices. I was very proud of my kids, because they're not used to giving speeches. The funny thing is that the little kids kept pointing at the boys. First of all they are big and blond. Then we realized they'd never seen braces. There were these white kids with metal teeth!

When William, who is actually kind of a small man, realized that our Pete -- who is big even by American standards -- was 13 and would be in that school if he lived there, he just couldn't get over that fact! He made all the other boys in that school who are 13 come and stand next to Pete to show ho huge he was!

They are very direct! And they were very surprised that I am a math teacher. 'Look at this woman! This woman is a professor. This woman does math!'

Harold did a great thing. Their school motto is 'Together we succeed'. Harold said, 'How about we all hold hands? It was just magical!

Harold: 400 hundred people are all holding hands and we raised our hands up and said, 'Together we succeed.' That was a very powerful moment, especially because we got so much accomplished and they felt so strongly about their connection to Lansing. And the difficulties that we had in getting there made a deep impression on them.

Cindy: The Africans are very formal. They like speeches, so there was another speech for the parents. But at one level it was gratifying for us beyond those sort of good feelings that we can assure everyone that that money made it there. The classrooms are there. You always wonder...

We saw them, and he talked about it to the parents, so if there were anything going on it wouldn't be that public.

Harold: There was a certain amount of money that went over there. And then you see eleven classrooms, a library, an administration building. Well, if you can build a classroom for $5,000 and you see the classroom, then you know the money is being spent with no creaming off. Everything was very open and above the table.

Cindy: My kids were all looking at their watches, timing how long it would take me to cry. (Laughs) I think Marlene won! It was overwhelming, because we've spent a lot of our time and energy thinking about this. you know it's real, but to actually see it and meet the people. People who are so gracious. They would come up and they knew our names and they had been thinking about us and what we did. They really had this sense of we didn't have to do this. Why did we do this?

They feel like Americans are so privileged, why should we care. If I live in a nice house and a nice community and we have good schools, why are we spending time doing this? The fact that we are just makes a huge impression. People would thank us.

The van Es family with Principal William Kabbis

Harold: It's not only because there are classrooms and the library. It is also because it has lifted the spirits of the community. The name Lansing means so much to those people in that whole area. Lansing is a magical name there. You really felt like you really made an impact.

We tried to focus on something that would be durable. These classrooms will be there for 30 years from now.

Cindy: William kept saying, 'This gave us a big boost.' He used that phrase a lot.

You got the sense it gave them a boost emotionally and physically as well as materially. Some people would come up, especially because we made it though all the danger. They's say they were praying for us. And some people literally thought it was a miracle that we had made it.

That's an indescribable thing having somebody look at you and think you are the result of some miraculous thing. I had a very hard time with that. I thought, no, I'm just a little math teacher from upstate New York.

But they just could not believe we had made it. So it added another dimension, that while all this was going on we were still able to get there.

There were some really scary moments. On that tarmac at Kisumu when we weren't sure we'd get out I prayed, 'Please don't let my children get hurt. Let us get out of here.'

When we went back to Kisumu and went to fly home all the riots started, and it was hard. The police are the opposition tribe. The military were coming in, and they're with the President. The people at the airport were taking bribes. So you don't know whether you can trust the airline people, the police, the military -- it's not quite the same as we're used to.

We flew back to Nairobi and then we had to be put in a secure vehicle to get back to our hotel. It's surreal, because you're in this beautiful garden hotel but all this is going on around you. You can see military troops going by and you hear gunshots. We were sitting in this garden area, kind of shaken up. We looked at the table next to us and there was the President of the World Bank, and we went around the corner and there was Desmond Tutu!

Harold: We were watching CNN and they interviewed people and the next morning they would be having breakfast at the next table.

Cindy: It was bizarre in that sense.

The family made it home to Lansing on January 10th. Now they plan to bring Principal Kabbis to Lansing to meet with our principals here and learn about the academic program at our schools. Originally they planned to bring him here this Spring, around now, but because of the unrest in Kenya he could not get to Nairobi to get his passport and visa. The van Ess say that they will use a separate fund donated by the IthacaRotary Club to bring him over.

Meanwhile they are continuing to raise money for the Kenyan school. They hope to fill the new library with books, and even endow a librarian position for it. Meanwhile the couple hopes that other communities will use PALS as a model for their own programs. With one year to go in their five year plan, PALS has largely reached the goals they originally set for the program. It will make a good model for other American schools that want to partner with African schools in need.

Photographs courtesy of Harold and Cindy van Es

----

v4i19