- By Dan Veaner

- Opinions

Print

Print  The Lansing Star has talked with Cargill for years about doing a Cargill feature including a mine tour for years, but they are not given that often. Last weekend more than 200 Cargill employees were invited to bring a guest for a mine tour, and 120 took the company up on it. 242 people were shown the mine including Karen (our staff photographer) and I (our staff reporter). We were were delighted to be invited along.

The Lansing Star has talked with Cargill for years about doing a Cargill feature including a mine tour for years, but they are not given that often. Last weekend more than 200 Cargill employees were invited to bring a guest for a mine tour, and 120 took the company up on it. 242 people were shown the mine including Karen (our staff photographer) and I (our staff reporter). We were were delighted to be invited along.Mine Manager Russ Givens showed us and his fiancée, his guest for the day, around. We were lucky -- Russ has an encyclopedic knowledge of the operation and history of the mine, so we got a comprehensive lesson on what the company does. We were underground for about three hours. An article in this issue goes into detail about the mining operation, but here is what it felt like to be 2300 feet underground.

When Karen and I arrived at Cargill on Sunday afternoon, we were escorted into a meeting room near the elevator shaft that would take us down into the mine. We were shown a safety video and signed a release before we geared up. We were each issued an identification number embossed in brass, kind of like a dog tag, that matched a sign-in sheet. We had to don a miner's belt with an emergency self-rescuer breathing device and a lamp battery, a hard hat with a miner's light, and a yellow reflective vest. The belt was a bit heavy, and I was concerned my pants would fall down.

Me and Mine Manager Russ Givens (right) suiting up before descending to the mine. At right is the vehicle we rode in as we tooled around the mine

Me and Mine Manager Russ Givens (right) suiting up before descending to the mine. At right is the vehicle we rode in as we tooled around the mineThe elevator is no-frills with a metal door and a hoist that is used to fit trucks and other equipment into the cabin. It is a two-story affair, and you can see the rock go by as the car descends into the mine. The five minute ride is a bit bumpy because the shaft is not 100% straight. It's not bad, though -- it's a bit like having to stand when riding the subway. It's dark in the mine, but we got used to it quickly.

We brought jackets, but we didn't need them. The atmosphere was a lot more comfortable than the outside air with the warm, humid weather we've been having recently. The mine is comfortable at 75 degrees year round, with about 10% humidity. The only time you feel chilly is during the drive, because the vehicles have no windows.

In a world where we are taught to look another person in the eye when we're talking to them, that is a problem underground, because the helmet light shines in the other person's eyes. Russ told us some veteran miners deal with this by wearing their helmets slightly to one side. Punk mine fashion. Cool!

The mine floor is covered with what appears to be sand, though of course it is salt. In areas separated by doors the air pressure is so great that special rounded doors are needed, because the whole mine is a huge circuit of air, all of which has to be pumped through the tunnels.

Around newly blasted areas you can smell a faint chlorine smell if you pay attention. That is from explosives that are primarily made of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil. Unfortunately for me my sense of smell is my keenest sense, but I didn't notice it until Russ mentioned it.

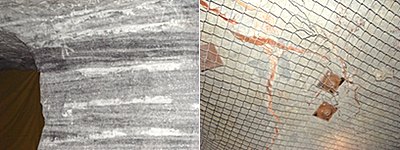

Pillars appear striped because they are periodically scraped to remove loose material. Ceilings are supported with bolts and loose shale is kept from falling on your head by chain link fence fastened to the ceiling.

Pillars appear striped because they are periodically scraped to remove loose material. Ceilings are supported with bolts and loose shale is kept from falling on your head by chain link fence fastened to the ceiling.As you are riding from the shaft to the working area, you see roof bolts every four feet that have been drilled four or five feet into the rock ceiling to reinforce it so it will not cave in. Expansion anchors made in Syracuse hold the bolts in place. Each bolt can support 22,000 pounds.

The 30 to 40 minute ride from the shaft to the working areas is bumpy with plenty of potholes, and with few exceptions it is dark. The only light comes from the lights on our miner's helmets and the headlights of the truck we rode in. It was also surprisingly quiet. That is not as true when drilling and blasting is going on, but it was surprising that there were no noticeable echoes. While some maintenance was being performed Sunday, no actual drilling or blasting was done on Sunday. So we didn't need masks because the air wasn't very dusty.

Moisture in the air that is forced through the tunnels erodes the shale that is above the salt layers. Chain link fence is installed on some of the ceilings to prevent shale chunks from falling on miners and their equipment. The equivalent of ten miles of chain link fencing is installed on mine ceilings.

There aren't many enclosed rooms in the mine, but the ones they have look like boxes sitting on the ground. They have lights, computers, wifi -- everything you would need. An electrical switching room is air conditioned to protect the equipment that controls power throughout the mine. The most primitive facilities are porta potties.

Miners work in relatively solitary groups of three, but there are enclaves where they can congregate, make calls, eat meals, use computers, etc. Givens says that depression caused by the darkness and isolation or fear of the enclosed space is not normally a problem. A week of training includes two days in the mine, starting with a tour, and including time in a production panel that includes experiencing blasting. He says when he trained in the '90s one of the new miners didn't like the explosions one bit.

"He flipped right out, Givens says. "He couldn't wait to get up to the surface. He got off that cage, dumped his gear on the ground and said, 'Thanks, but I'm not working here.' But it's rare that we run into that."

We thought the mine was surprisingly comfortable. Karen noted the only flaw in the day was that we didn't find any Hobbits down there, but I thought it was decent that we also didn't encounter Morlocks. And good news: my pants didn't fall down.

Photos by Karen Veaner

v836