- By Maja Anderson

- Around Town

Print

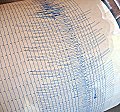

Print  The Museum of the Earth at the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) has on display a seismogram from the devastating earthquake that hit Japan last week. The threat of further seismic shifts and tsunamis continue and meteorological agency officials warn of likely aftershocks in the region. The Museum of the Earth is able to track earthquakes in real time using its onsite seismometers.

The Museum of the Earth at the Paleontological Research Institution (PRI) has on display a seismogram from the devastating earthquake that hit Japan last week. The threat of further seismic shifts and tsunamis continue and meteorological agency officials warn of likely aftershocks in the region. The Museum of the Earth is able to track earthquakes in real time using its onsite seismometers.The March 11, catastrophic event in Japan began as a seismic shift which permanently moved Honshu Island, the island closest to the epicenter of the quake, a distance of 8 feet. The Pacific plate off the coast of Japan, which is slowly but constantly sliding underneath the North American plate, shifted 8 feet in only a few minutes and caused the massive earthquake and subsequent tsunami that enveloped coastal areas.

A seismometer records the enormous amounts of energy that travel through the Earth in the form of seismic waves. Most seismometers work with a mass which can move relative to the frame of the instrument. When a seismic wave arrives at a seismograph station, the frame (which is fixed to the solid earth) moves with the earth but the mass does not because of its inertia. PRI's seismometers are located on a concrete pier in their Seismology Room. The motion created by Earth’s waves moves a magnet over a coil. As the magnet moves back and forth over the coil, the coil generates a voltage.

The signal is recorded digitally, or, in the case of analog seismographs, a pen moves back and forth on a rotating drum covered with paper. The resulting image mimics the pattern of the waves sensed by the seismometer. The analog seismographs at the Museum of the Earth were installed by faculty from Cornell's Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, which is renowned for its research in seismology and tectonics. PRI's digital seismometer is operated on behalf of the Lamont Cooperative Seismic Network, run by Columbia University, and can be viewed online (choose the station "PRNY" and click "submit").

Much of the Museum of the Earth’s permanent exhibition illustrates the history of Earth systems, which include life in addition to the solid Earth, oceans, and atmosphere. Seismometers are essential for understanding the internal structure of the earth and the process of plate tectonics, which has shaped the history of our planet, including our own local rock record.

v7i11